Small Planet Communications, Inc. + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact

The history of Africans and those of African descent born in the Americas is an essential part of the history of the New World—and a complicated story. Soon after the “discovery” of the New World in 1492, Africans arrived and made their influence felt. They helped explore both South and North America and build settlements—and were essential for the survival and growth of colonies in both continents. Some Africans who arrived in the New World are thought to have come over freely, but most were brought over the Atlantic Ocean as enslaved people.

Visit Documenting the American

South, a website sponsored by

the University of North Carolina

featuring links relating to slavery,

including a collection of slave

narratives.

The history of slavery is also a complicated story—one that is over 10,000 years old—and one that continues even today, worldwide. Slavery did not originate in colonial America, or even in the Americas or Africa, but evolved over time and throughout the world as human societies developed. For example, during ancient times, women who had been captured as a result of war or conquest were typically enslaved; male captives were usually killed. Ancient Greece and Rome relied on the enslavement of people as sources of labor and to help expand their empires. Ancient African nations also enslaved captives of war or used enslavement as punishment for certain crimes.

However, until Europeans appeared in Africa in the 15th century, African slavery was a different and much smaller-scale institution. Under the African system, some slaves served as soldiers or craftspeople, and most were treated well and worked as farmers. Profound differences emerged as the plantation system of slavery developed in colonial America.

Click on this timeline by Durham

University (Durham, England).

Explore this interactive timeline

by the National Geographic Society.

The beginnings of slavery in the American colonies were tied to the labor needs of English settlers. In Virginia, the first permanent English colony, colonists needed a large supply of workers to pick tobacco and clear forests, among other tasks. They turned toward a familiar English institution—indentured servitude. In England, apprentices were trained to be craftsmen by entering into a contract with a master of a craft, who taught the apprentice a skill. It was a system that helped educate and train many young people who did not have the money to pay for school or university. Once their apprenticeship was complete, apprentices could work for anyone and eventually set up their own businesses.

DID YOU KNOW?

Slavery was legal in all 13 of

the original colonies. Many of

our founding fathers owned

slaves, including George

Washington and Thomas

Jefferson.

Indentured servitude was neatly adaptable to the colonial need for labor. For the small cost of trans-Atlantic passage and various brokers' fees, a tobacco farmer could secure the services of a servant for between five and seven years. A majority of servants, who were members of England's lower classes, were more than willing to trade a few years of their lives in exchange for a fresh start. However, the practice of filling the hold of a servant ship by kidnapping boys or careless adults in English seaports was common. English courts also sentenced criminals convicted of petty crimes to become indentured colonial servants.

During the early 1600s, colonial slavery was a much different institution than that closer to the Civil War. Some enslaved African were put to work on plantations, while others were treated like European indentured servants and freed after a period of service. By the late 1660s, however, the supply of indentured servants began to dwindle. Meanwhile, English sugar cane growers in the West Indian colony of Barbados began following the example of Brazilian sugar plantations and buying captured Africans as enslaved workers. By the 1670s, the colonies of Maryland and Virginia each had nearly two thousand enslaved Africans or African Americans (people of African descent who had been born in the American colonies). England began importing slaves directly from Africa, and colonial assemblies began passing laws to turn African indentured servants into slaves. This was due in part to the high demand for tobacco and the fact that many European indentured servants died from diseases such as smallpox or influenza within a few years of arriving in the colonies. Africans seemed less vulnerable than Europeans to subtropical diseases, particularly malaria and yellow fever.

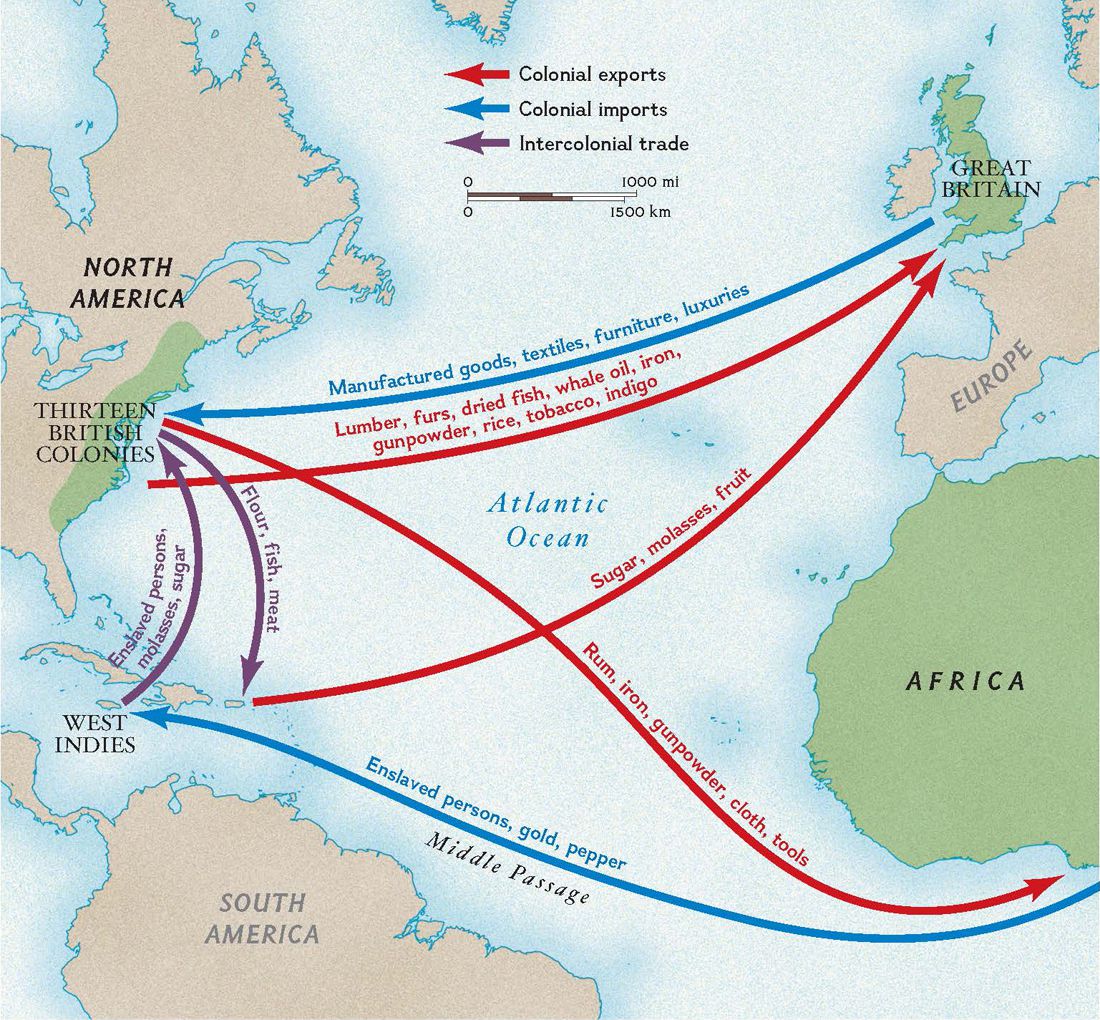

Visit this link to see another Triangular Trade Map

and to access more information.

Read about Triangular Slave Trade. Then follow the

personal stories of four enslaved Africans.

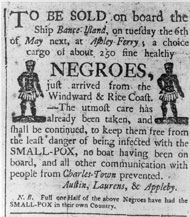

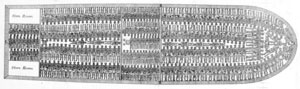

Quarters on a typical slave ship during the Middle

Passage were very tight. Click to view images related

to slave ships and the Atlantic Crossing.

Most slaves came from west African nations in the interior that were at war with coastal states. Despite common misconceptions that European traders raided villages to capture slaves, most Africans were enslaved by other Africans. The majority of slaves were prisoners of war, victims of bandits, or criminals receiving punishment for minor crimes or religious offenses. While some professional slave traders did raid African villages, most traders constructed bases on the west African coast, where they bought slaves in exchange for guns and other items.

The long, nightmarish journey of captured Africans across the Atlantic formed the "middle passage" of what became known as the triangular trade. The "Middle Passage" was the middle part of the three-part voyage that began in Europe, when ships loaded with items such as cloth, brandy, and firearms sailed to Africa's "slave coast." The cargo was then traded for slaves, and the ships sailed for the colonies, where the slaves were traded for sugar, tobacco, or other goods. The ships then sailed back to Europe. During the voyage, slaves were shackled and branded with hot irons. Three to four hundred slaves were often packed in a tiny, cramped area below deck, with virtually no headroom and little ventilation. The horrors of the experience made many slaves want to die, but because the human cargo was so valuable, ships' captains did all they could to keep slaves alive. Still, it is estimated that between ten and twenty percent of slaves died during the "Middle Passage."

Upon arrival in the colonies, enslaved Africans found themselves in a society that viewed them as private property and was organized to keep them that way. There were many challenges to endure—being sold at auction, being separated from family members, settling into a new way of life, struggling with a foreign language, and undertaking the daily labor for which they had been seized. The life of a slave was dominated by this one activity.

Besides plantation and agricultural tasks, many enslaved people worked in mines, fished, piloted boats, labored in dairies, drove livestock, and even operated printing presses. Enslaved Africans brought the skills and trades they had learned in their homelands to the colonies, which helped industry and agriculture to grow quickly. For example, many slaves knew how to grow rice, which was unfamiliar to many Europeans. Without the skills and expertise of enslaved Africans and those of their descendants, large-scale rice fields in South Carolina and Louisiana would not have succeeded.

The picture above shows slave

quarters. Read more about their living

conditions, education, and religion.

Another important aspect of African-American culture was religion. Before 1750, European Americans made only small attempts at converting slaves to Christianity, fearing that, among other things, conversion might change a slave's legal status, even though most colonies had passed laws against this possibility. Therefore, for most of the colonial period, slaves were largely left alone in regard to spiritual and religious practices. There were many differences between African religions and Christianity. For example, Africans generally believed that their ancestors' spirits remained as members of the family and community and that they needed to be recognized and honored. As most had done in Africa, slaves often came together to share stories, worship God, and pay respects to their ancestors through music and dancing.

Whereas slave owners did not bother to offer religious instruction, slaves increasingly filled the gap. Beginning with religious revivals in the 1730s and 1740s, many slaves converted to Christianity. The religion gave them hope in a difficult world, and fused with African musical traditions, it led to the creation of spirituals—songs that slaves sang during their daily work tasks and which served as both music and proverbs for slave communities. Slave owners also eventually began to view Christianity among slaves more favorably because it seemed to make slaves work harder at their jobs.

Click to learn more about

the Stono Rebellion and

other slave revolts.

Most Southern slaveholders lived in fear of a major slave rebellion, but in most cases enslaved people resisted by acting against their owners in small ways that were aimed at causing the owners trouble or discomfort. Slaves would often break tools, pretend to be sick, or perform acts of sabotage and arson. Some slaves also ran away from their masters. Many headed south or hid in densely-forested swamps where they could not easily be caught. During the colonial period, fugitive slaves organized communities called "maroon colonies" that were hidden in swampy, mountainous, or frontier areas. In 1739, a famous revolt took place—the Stono Rebellion—in which an organized group of slaves headed for Spanish Florida, seeking to escape from the colony of South Carolina.

As widespread as slavery was, every colony also hosted a population of free African Americans. Some had bought their freedom, while others had escaped or lived in places that had abolished slavery. Being a free African American was far from enviable, even when compared to being a slave. There were few legal protections, even in supposedly free states, and the threat of being kidnapped and returned to slavery was always present. Despite these obstacles, freed African Americans worked in trades including construction, metalworking, and retail, while others founded schools and universities whose graduates eventually led the campaign to abolish slavery during the 19th century.

- African American Registry. "Lucy Terry Prince, Poet, Abolitionist, Orator Born." Accessed 6/17/19.https://aaregistry.org/story/lucy-terry-prince-poet-abolitionist-orator-born

- Alexander, Kerri Lee. "Elizabeth Freeman." National Women’s History Museum. Accessed 6/14/19.https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-freeman

- Ault, Jon. "Bound to Serve: Eighteenth-Century Native Indentures in Archives." Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center.

- BlackPast.org. “Anthony Johnson.” Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/johnson-anthony-1670

- Bonomi, Patricia U. "Religious Pluralism in the Middle Colonies." National Humanities Center. Accessed 6/12/19. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/

tserve/eighteen/ekeyinfo/midcol.htm - Boston Massacre Historical Society. "Crispus Attucks." Accessed 6/13/19. http://www.bostonmassacre.net/players/crispus-attucks.htm

- The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). "Olaudah Equiano." Accessed 6/14/19. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/equiano_olaudah.shtml

- The Crispus Attucks Association. "The History of Crispus Attucks as a Man." Accessed 6/13/19. http://crispusattucks.org/about/who-was-crispus-attucks

- DeFord, Susan. "How the Cradle of Liberty Became a Slave-Owning Nation." Washington Post, December 10, 1997. Accessed 6/12/19. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1997/12/10/how-the-cradle-of-liberty-became-a-slave-owning-nation/e53b3e62-6f39-432e-ae17-0e58abbcca47/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.33589a490023

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Benjamin Banneker." Accessed 6/13/19. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Benjamin-Banneker

- Eschner, Kat. "The Horrible Fate of John Casor, the First Black Man to Be Declared Slave for Life in America." Smithsonian.org. Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/horrible-fate-john-casor-180962352

- Facing History and Ourselves. "Anthony Johnson: A Man in Control of His Own." Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/anthony-johnson-man-control-his-own

- Facing History and Ourselves. "We and They in Colonial America." Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-2/we-and-they-colonial-america

- Giblin, James. "Issues in African History." University of Iowa. Accessed 6/12/19. http://web.archive.org/web/20140112083458/http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/history/giblinhistory.html

- Gilder Lehman Institute of American History. "The Americas to 1620." Accessed 6/12/19. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/americas-1620

- Gilder Lehman Institute of American History. "The Origins of Slavery." Accessed 6/12/19. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-now/origins-slavery

- Glaser, Leah S. "Early European Exploration and Colonization." Virginia Center for Digital History: Miller Center of Public Affairs. Accessed 6/13/19. http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/solguide/VUS02/essay02.html

- Guasco, Michael. "The Misguided Focus on 1619 as the Beginning of Slavery in the U.S. Damages Our Understanding of American History." Smithsonian.org. Accessed 6/13/19. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/misguided-focus-1619-beginning-slavery-us-damages-our-understanding-american-history-180964873/

- Holt House Slavery Research Project. "Chronology on the History of Slavery and Racism." Accessed 6/12/19. https://www.scribd.com/doc/54602595/Chronology-on-the-History-of-Slavery-1619-to-1789

- Jacoby, Daniel. "Apprenticeship in the United States." University of Washington, Bothell. Accessed 6/12/19. http://eh.net/encyclopedia/apprenticeship-in-the-united-states/

- Library of Congress. "The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship." Accessed 6/13/19. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/slavery-the-peculiar-institution.html

- Library of Congress. "Immigration. . . Beginnings: Explorers and Colonists." Accessed 6/13/19. https://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/alt/african2.html

- Library of Congress. "Immigration: Africans in America." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/

presentations/immigration/african4.html - Mass Humanities: Mass Moments. “August 28, 1748: Lucy Terry Prince Composes Poem." Accessed 6/17/19. https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/lucy-terry-prince-composes-poem.html

- Mass Humanities: Mass Moments. “May 1, 1777: Agrippa Hull Enlists." Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/agrippa-hull-enlists.html

- Mass Humanities: Mass Moments. "August 22, 1781: Jury Decides in Favor of Elizabeth 'Mum Bett' Freeman." Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/jury-decides-in-favor-of-elizabeth-mum-bett-freeman.html

- Michals, Debra, ed. "Phillis Wheatley." National Women's History Museum. Accessed 6/17/19. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/agrippa-hull-revolutionary-patriot/

- Nash, Gary B. "Agrippa Hull: Revolutionary Patriot." BlackPast.org. Accessed 6/14/19. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/phillis-wheatley

- National Academy of Sciences: African American History Program. "Benjamin Banneker." Accessed 6/13/19. http://www.cpnas.org/aahp/biographies/banneker-benjamin.html

- The National Archives United Kingdom. "West Africa Before the Europeans." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/

africa_caribbean/west_africa.htm - New Jersey State Library. "African American Slavery in the Colonial Era, 1619–1775" by the New Jersey Historical Commission. Accessed 6/13/19. https://www.njstatelib.org/research_library/new_jersey_resources/highlights/african_american_history_curriculum/unit_3_colonial_era_slavery/

- O'Neale, Sondra A. "Phillis Wheatley." The Poetry Foundation. Accessed 6/17/19. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley

- Proper, David R. "Lucy Terry Prince: Singer of History." The Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and Historic Deerfield, Inc. Accessed 6/17/19. http://www.memorialhall.mass.edu/classroom/curriculum_12th/unit1/lesson9/lucy_terry.html

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). "The African-American Migration Story." Accessed 6/12/19. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/on-african-american-migrations

- Restavek Freedom. "The History of Slavery." Accessed 6/12/19. https://restavekfreedom.org/2018/09/11/the-history-of-slavery/

- Robinson, Yonaia. "Elizabeth Key Grinstead." Accessed 6/17/19. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/grinstead-elizabeth-key-1630

- Slavery and Remembrance. "Elizabeth Key (Kaye)." The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Accessed 6/17/19. http://slaveryandremembrance.org/people/person/?id=PP031

- University of Denver, The Spirituals Project. "Sweet Chariot: The Story of the Spirituals." Accessed 6/12/19. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7728/20160809204827/http://www.spiritualsproject.org/sweetchariot/History/index.php

- University of Houston, Digital History Project. "The Origins and Nature of New World Slavery: Enslavement." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3033

- University of Houston, Digital History Project. "The Origins and Nature of New World Slavery: Slave Resistance and Revolts." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3045

- University of Houston, Digital History Project. "The Origins and Nature of New World Slavery: Slavery in Africa." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3030

- University of Houston, Digital History Project. "The Origins and Nature of New World Slavery: Slavery in Colonial North America." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3036

- University of Houston, Digital History Project. "The Origins and Nature of New World Slavery: Slavery's Evolution." Accessed 6/12/19. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3037

- University of North Carolina: Documenting the American South. "Olaudah Equiano." Accessed 6/14/19. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/equiano1/summary.html

- USHistory.org. "The Growth of Slavery." Accessed 6/13/19. http://www.ushistory.org/us/6c.asp

- Vermont Historical Society. "Lucy Terry Prince." Accessed 6/17/19. https://vermonthistory.org/research/vermont-women-s-history/database/prince-lucy

- Triangular Trade Map | National Geographic Society; "Colonial Trade Routes and Goods"

- Slave Ship Diagram | Thomas Clarkson, author (1808); University of Virginia Special Collections

- Advertisement for Slave Sale | South Carolina Gazette, circa 1780; The Library of Congress

- Slave Quarters | Kingsley Plantation, Duval County, Florida; SlaveryImages.org courtesy of the New York Historical Society

- The Boston Massacre | The Bostonian Society; W.L. Champney's Massacre Print, 1856

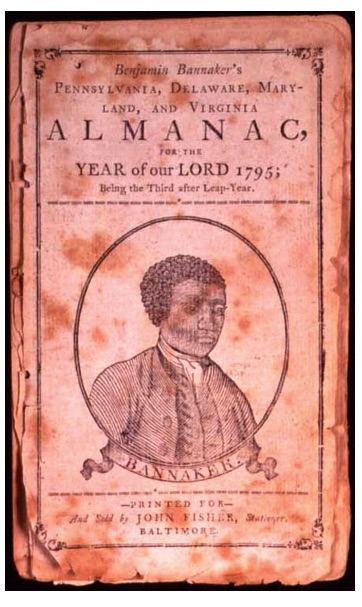

- Cover, Benjamin Banneker's Almanac for 1795 | The Library of Congress; Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore

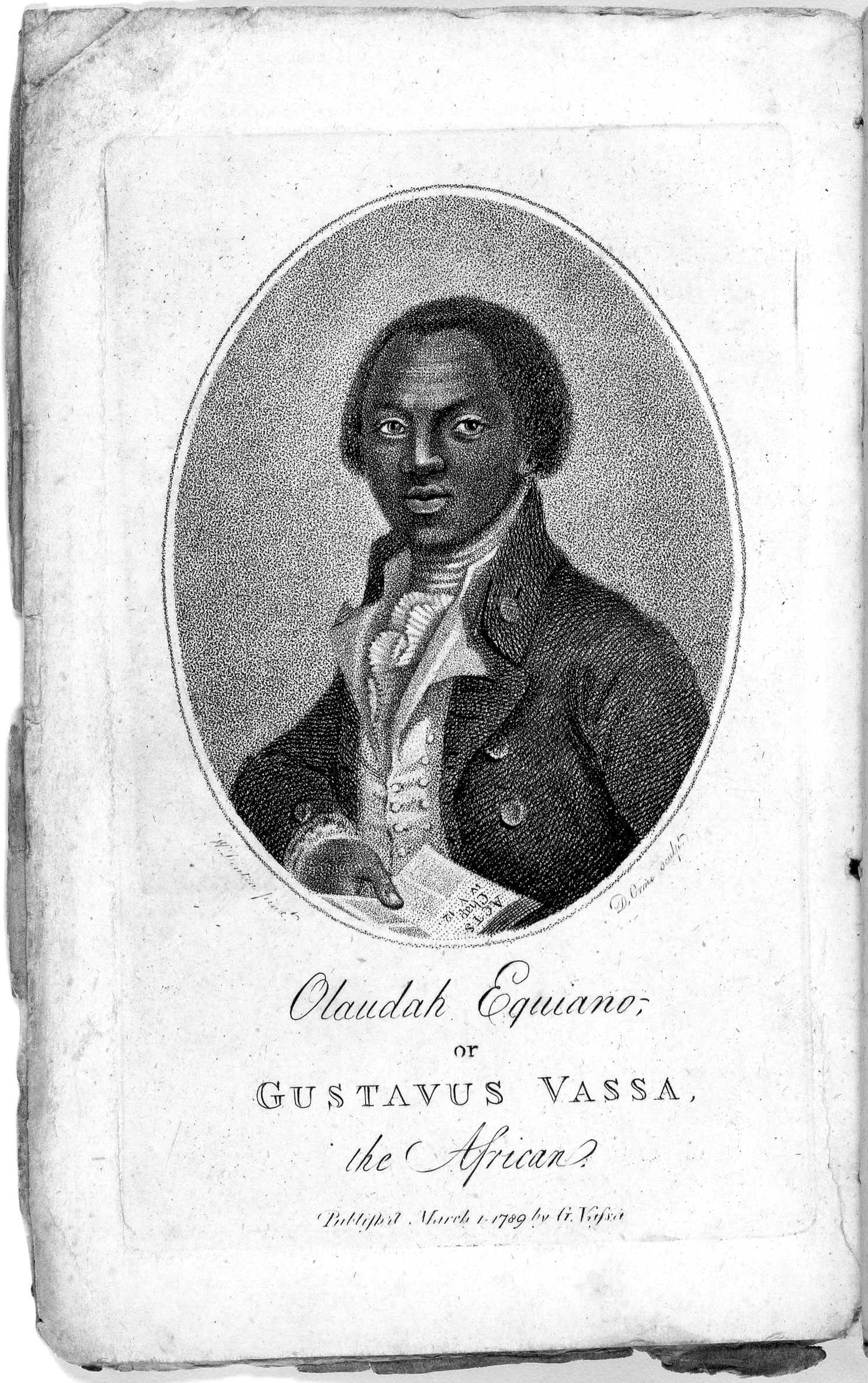

- Cover, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1794) | Olaudah Equiano; The Library of Congress

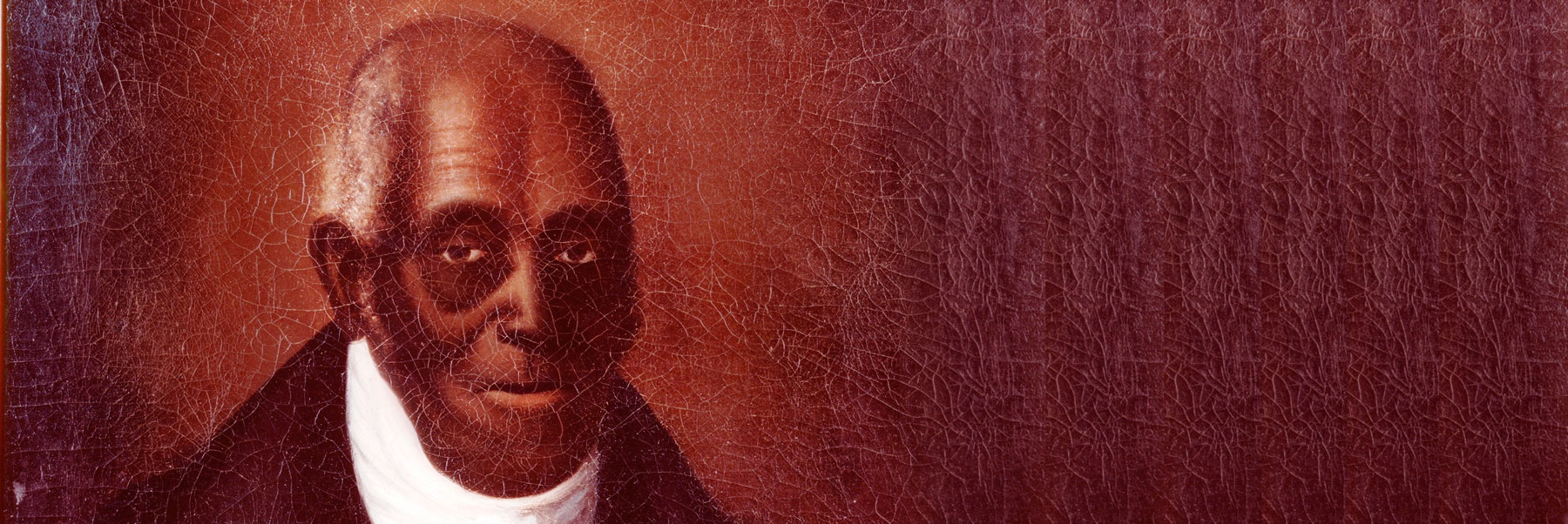

- Elizabeth Freeman (age 70) | Painted by Susan Ridley Sedgwick (c. 1812); Massachusetts Historical Society

- Portrait of Agrippa Hull | Stockbridge Library Association Historical Collection

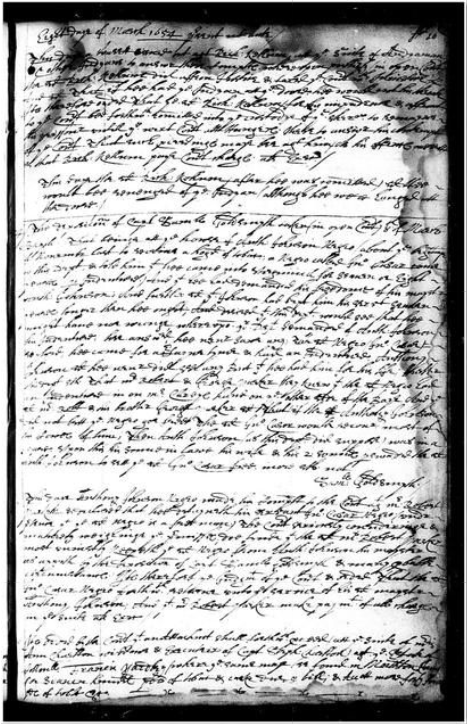

- Handwritten court ruling, March 8, 1655 | Courtesy of Library of Virginia

- Virginia Tobacco Field and Tobacco Barn | Library of Congress

- The Ebenezer Wells house, Deerfield, Massachusetts; Where Lucy Terry Lived and Worked | Tracing Center

- Statue of Phillis Wheatley, dedicated 2003, Boston Women’s Memorial | Friends of the Public Garden

Some Notable African Americans of the Colonial Era

This print from the 1850s commemorated the deaths of Crispus Attucks

and four others in the Boston Massacre of 1770.

Attucks, Crispus (c. 1723–1770) Working as a merchant sailor after having escaped slavery, Attucks led a group of dock workers and sailors in Boston as part of a protest against British troops. Attucks was fired upon and killed as were four other protestors. Attucks is considered the first casualty in the American Revolution. The deaths of Attucks and the four others in the Boston Massacre served to rally Americans in their fight for independence.

1795 Almanac cover

by Benjamin Banneker.

Banneker, Benjamin (1731–1806) Banneker was born into a free African American family in Baltimore County, Maryland. Mostly self-taught, he became an accomplished mathematician, scientist, and inventor. Banneker was a key member of the team that surveyed and laid out the plans for the creation of Washington, D.C., to serve as our nation’s capital. He also published a popular almanac and corresponded with Thomas Jefferson (as the author of the Declaration of Independence), urging equal treatment

for all African Americans.

1794 cover of Equiano’s autobiography,

The Interesting Narrative of the

Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus

Vassa, the African.

Equiano, Olaudah (c. 1745–1797) Equiano spent much of his life at sea, as an enslaved sailor and then after having bought his freedom as a free man. His voyages took him all over the world and included one that explored the Arctic, hoping to find the elusive Northwest Passage. In 1786, he settled down in London, England, and married. Equiano became active in the abolitionist movement and wrote an autobiography to support the efforts to end slavery. His book also became a best-seller, earning him great fame and wealth.

Portrait of Elizabeth Freeman, age 70,

by Susan Ridley Sedgwick (c. 1812).

Freeman, Elizabeth (c. 1742–1829) Born into slavery as "Mum Bett,” Bett lived in Western Massachusetts and believed that she had a strong legal case for freedom after ratification of the state constitution of Massachusetts in 1780. She enlisted legal help and brought a lawsuit against her owner in a Massachusetts court. After the hearing, the jury decided that Bett should indeed be free. Upon winning her freedom, Bett changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman. Her “freedom suit” paved the way for others, which ultimately led to the abolishment of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783. Once the first colony to legalize slavery, Massachusetts became one of the first states to abolish it—as a result of Freeman’s efforts.

Photo of Virginia tobacco field and barn.

Grinstead, Elizabeth Key (1630–1665) Elizabeth Key’s father was a white Virginia tobacco planter; her mother one of his African indentured servants. When Key was claimed as a slave later in her adult life—rather than freed as an indentured servant who had served her contract—she brought one of the earliest lawsuits—a freedom suit—to win her freedom in court. In 1656, Key won her case, mainly because her father was a freeman and because she had been baptized in the Christian faith as a child. Key then married William Grinstead (sometimes noted as Grinsted or Greensted). However, by the late 1660s, the Virginia colony passed laws that required a child’s slave status be determined by the status of the child’s mother and that being baptized in the Christian faith could not free a person from enslavement. These laws institutionalized slavery in the Virginia colony; one result of which was to have enslaved labor for Virginia’s tobacco plantations.

Portrait of Agrippa Hull, Revolutionary War hero.

Hull, Agrippa (1759–1848) Signing on as an 18-year-old in the fight for American independence, the freeborn Hull become one of over 5,000 men of color to serve in the Continental Army for the war’s duration. Hull survived the brutal winter in Valley Forge and fought in many key battles, including Saratoga and the Siege of Charleston, while mainly serving under the Polish general Taddeusz Kosciuszko. After the war, Hull became a major landowner and prominent citizen in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Handwritten Virginia court ruling,

March 8, 1655, ordering John Castor

be returned to Anthony Johnson.

Johnson, Anthony (unknown–1670) Born in Africa, Johnson was kidnapped and brought to Virginia against his will around 1621, either as an enslaved laborer or as an indentured servant. By around 1651, Johnson had won his freedom and owned a large plantation. In a legal dispute, one of Johnson’s indentured African American servants, John Casor, was declared Johnson’s slave for life as the Virginia colony started to institutionalize slavery. When Johnson died in 1670, his plantation did not pass on to his children, but went instead to a white farmer—Virginia by that time had declared that black men were not citizens of the colony and thus had no rights to property.

The Ebenezer Wells house, Deerfield,

Massachusetts, where Lucy Terry lived

and worked until she gained her freedom.

Prince, Lucy Terry (c. 1724–1821) Kidnapped in Africa as a very young girl, Lucy Terry was sold into slavery and brought to Deerfield, Massachusetts. After a raid on Deerfield, Terry composed a poem about the events, called “The Bars Fight.” Terry’s poem is considered the first one composed by an African American. Her poem was passed on orally for generations before it was first printed in 1855. After marrying Abijiah Prince, a free African American, in 1756, Lucy Terry Prince gained her freedom. Lucy Terry Prince also won wide acclaim for her skills as a speaker and legal thinker as she successfully defended her family’s rights and property in court several times.

Statue of Phillis Wheatley, dedicated

2003, Boston Women’s Memorial.

Wheatley, Phillis (c. 1753–1784) Taken from her home in West Africa when she was a young girl, Wheatley was not considered strong enough to work in the island or southern colonies. She ended up enslaved in Boston, where she worked at domestic tasks, but also learned to read and write. Wheatley’s first poem was likely published in 1767, when she was just 13 or 14 years old. She continued to write poetry and her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in 1773. Wheatley’s book became the first book of poems published by an African American and only the second book of poems ever published in America by a woman. After Wheatley gained her freedom, she struggled economically, especially as the Revolutionary War raged on and an economic depression followed. Although Wheatley continued to write and publish her poems, she could only find work as a scrubwoman or a charwoman and died in poverty.

African Americans | Bibliography

African Americans | Image Credits

© 2020 Small Planet Communications, Inc. + Terms/Conditions + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + planet@smplanet.com