Small Planet Communications, Inc. + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + Contact

Read an account of the history of

the Pequot American Indians.

The Pequot (Pee-kwaat) lived along the Pequot (now Thames) and Mystic Rivers. Numbering around 6,000 in 1620, the Pequot were a powerful group—the name Pequot means "destroyers" in Algonquin. Accustomed to taking what they wanted from those around them, the neighboring Narragansett group was their only discernible rival.

In the early 1630s, settlers from English and Dutch colonies began to spread into the Connecticut Valley region in order to accommodate the increasing number of European emigrants. The continuing tide of settlement eventually brought the colonists into conflict with the Pequot nation that already inhabited the southeastern area of present-day Connecticut. Indeed, the Pequot viewed the Connecticut River and adjacent lands as their territory. The increased Dutch and English migration into the Connecticut Valley quickly erupted in disputes between European settlers and native inhabitants, as well as causing disagreements among the Pequot themselves.

At the same time, the beaver fur trade proved very lucrative for the Pequot, who eventually established relations with both English and Dutch traders. For a time, the Pequot had a near monopoly on trade in the area. However, beginning in 1633, the Pequot suffered a horrific smallpox epidemic. The deadly disease, against which the Pequot had no immunity, caused the Pequot to lose half of their people. The population loss also strained trading relationships.

Wampum, or beads made from shells,

were used to trade for furs and other goods.

Sometimes Europeans and American Indians

exchanged wampum in place of furs.

The conflict between the Europeans and the Pequot increased in 1634 when, despite an agreement with the Dutch not to interfere with trade, the Pequot murdered several Narragansetts who were trading at the Dutch trading post, House of Hope. The Dutch retaliated by capturing the Pequot grand sachem Tatobem, threatening to kill him unless the harassment of traders ceased. A ransom was also demanded. The Pequot paid the ransom, but nevertheless, the Dutch executed Tatobem. Sassacus, Tatobem’s son, became grand sachem. However, there were divisions in the Pequot tribe. Uncas, Sassacus's brother-in-law thought he should be sachem and challenged Sassacus. He did not succeed—at first.

According to Pequot custom, the Pequot people would have exacted revenge for Tatobem’s death by killing a Dutch person or asking for a payment as recompense. Instead, a few months later, Captain John Stone, an Englishman, was killed by the Niantic tribe, a western branch of the Pequot. Stone, who was a trader and a pirate, was the victim of a retaliation attack due to Tatobem's death. The English viewed Stone's murder as an act of war.

In November of 1634, a Pequot embassy headed by Sassacus met with the governor of Massachusetts Bay in an effort to make peace. In the Massachusetts Bay-Pequot treaty, the English agreed to establish trade with the Pequot and to mediate disputes with the Narragansett. The Pequot were to give up Connecticut lands, pay compensation of £250 sterling in wampum, and turn over the killers of Captain Stone. The Pequot council did not ratify the treaty, as they were unwilling to cede land in Connecticut and objected to the exorbitant indemnity. They also insisted that Stone's murderers were either dead or no longer in the area.

By 1635, several groups had emigrated from both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies. John Winthrop, the son of the Massachusetts governor, founded Saybrook at the mouth of the Connecticut River. This put the House of Good Hope out of business as the Dutch lost control of the river, and it effectively cut off Dutch support to the Pequot. English trader John Oldham and nine others from Watertown then settled Wethersfield. The following year, Thomas Hooker and his followers arrived in Connecticut and settled Hartford. Most of the American Indians were friendly to the colonists, as they welcomed the chance to escape the tyranny of the Pequot. The Pequot, however, saw themselves being overrun and losing control over other American Indian groups. Uncas, on the other hand, saw opportunity to achieve his goals by aligning himself with the English. He rebelled against Sassacus and eventually assumed the leadership of a small group known as the Mohegan (sometimes called Mohican).

In June 1636, Uncas, the Mohegan sachem, sent a message that the Pequot

were preparing to attack the English. In an effort to thwart this attack, a conference

at Fort Saybrook was convened in July. The meeting was attended by officials

from the Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay colonies and by Pequot and Niantic representatives. Although the Pequot pledged their loyalty to the English, nothing

was resolved as the English simply reasserted their demands from the aborted

1634 treaty.

Read more about John Oldham,

an English trader whose murder

sparked the Pequot War.

The precipitating cause of the Pequot War was the murder of John Oldham on July 20, 1636. Oldham and his crew were murdered in his boat off of Block Island. The English settlers vowed to retaliate against the American Indians, and on August 25, Massachusetts raised a military force under the command of John Endecott. This troop of 90 men attacked the Niantic village on Block Island. Most of the villagers fled, but 14 were killed.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Pequot War was

the first major conflict

between European

colonists and Native

Americans.

Endecott's expedition then sailed to Fort Saybrook. Despite protests from Lieutenant Lion Gardiner, Endecott's troops marched into the Pequot village where they restated demands of compensation for Stone's death, as well as Oldham's. The villagers managed to escape as Endecott launched an attack, destroying crops and setting fire to the village. After Endecott's company retreated to Massachusetts, the enraged Pequot group retaliated by attacking anyone trying to leave the fort. The siege continued intermittently through autumn and winter. The settlements on the Connecticut River were held in a state of constant fear as the Pequot plundered and murdered at

every opportunity.

Over the winter, Pequot sachem Sassacus tried to persuade the Mohegan and Narragansett to become his allies. The united tribes, he claimed, could organize four thousand men for battle, while among all the English in the Connecticut Valley, there were only a few hundred men capable of bearing arms.

View a different map of the Pequot War Battle Sites.

At this point, Puritan minister Roger Williams intervened. Following his banishment from Massachusetts, Williams had taken refuge among the Narragansett, with whom he had developed peaceful relations. Perceiving the danger of the proposed tribal alliance, Williams sailed across Narragansett Bay to the village of Miantonomoh near present-day Newport, Rhode Island. Williams debated with ambassadors from Sassacus, even though he risked his life in doing so. In the end, Williams kept the Narragansett from aligning with the Pequot. He persuaded Narragansett chiefs to go to Boston, where they concluded a treaty of peace and alliance with the colonists.

The Mohegan, led by Uncas, also made the decision to side with the English. Thus, the Pequot were suddenly alone in their fight against the settlers. The Pequot had only a few guns and little powder. The English colonists had guns, swords, armor, large numbers fighters, and the support of the surrounding American Indian people.

In April 1637, Pequot members attacked a group of settlers working in a field near Wethersfield, killing nine and taking two teenage girls captive. They had now slain more than 30 settlers and were forced to choose between flight and destruction or war and possible victory.

The Connecticut General Court met at Hartford on May 1, 1637. The result was the decision to declare war against the Pequot. A draft of 90 men was ordered from the area to be under the command of Captain John Mason. They joined the company headed by Captain John Underhill, who led the combined forces of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies. Seventy Mohegan warriors led by Uncas also joined

the group.

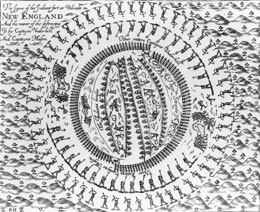

Read about John Underhill's accounts of the

attack on the Indian Fort.

With the aid of Mohegan and Narragansett allies, the colonists launched a surprise morning attack on the Pequot stronghold at Mystic River on May 26, 1637. Before the villagers were fully awake, Mason and Underhill's troops surrounded the village, setting it on fire. The terrified Pequot rushed out of their dwellings fleeing the flames only to be driven back by swords and musket-balls. Between 500 and 600 Pequot men, women, and children, perished in the flames.

When an even larger group of Pequot was trapped in a swamp, the Puritans did not hesitate to kill the fighting men. The few surviving Pequot fled. Most were eventually killed. The women and children were captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies. Sassacus and the few who escaped with him were put to death by Mohawk Indians after being captured near Fairfield, Connecticut, on July 28, 1637. The head of Sassacus was sent to the English as a token of friendship. From that point on, the Mohegan took possession of all Pequot land.

The Treaty of Hartford officially ended the Pequot War. The surviving Pequot were disseminated into surrounding tribes. They were forbidden to live on land previously owned by the Pequot, and they were no longer allowed to call themselves Pequot. The Pequot today number around 1,000 and are associated with the Mashantucket line (Western Pequot) and the Pawcatuck line (Eastern Pequot). After gaining a large settlement over land disputes in 1970's, the Mashantucket Pequot established a lucrative gaming and gambling casino. They are among the wealthiest Native American groups in the United States today.

The Pequot War | Bibliography

- Battlefields of the Pequot War. "The History of the Pequot War." Accessed 6/19/19. http://pequotwar.org/about/

- Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation. "Tribal History." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.mashantucket.com/tribalhistory.aspx

- Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation. "The Pequot War." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.mashantucket.com/pequotwar.aspx

- Mystic Voices: The Story of the Pequot War. "The History." Accessed 7/10/19. http://www.pequotwar.com/history.html

- Montagna, Joseph A. "The Indians of Connecticut." The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Accessed 6/19/19. http://colonialwarsct.org/ct_indians.htm

- Plimoth Plantation. “Plymouth & Patuxet Ancestors.” Accessed 6/19/19. https://www.plimoth.org/learn/just-kids/plimoth-patuxet-ancestors#sources

- The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. "1637—The Pequot War." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.colonialwarsct.org/1637.htm

- Sultzman, Lee. "History of the Pequot Indians." The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.colonialwarsct.org/1637_pequot_history.htm

- Surprenant, Donald J. "The Constitution State." The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.colonialwarsct.org/constit_state_political.htm

- United States Wars. "The Pequot War (1637-1638)." Accessed 6/19/19. http://www.uswars.net/pequot-war/

- World History Project. "Pequot War Timeline." Accessed 6/19/19. http://worldhistoryproject.org/topics/pequot-war

The Pequot War | Image Credits

- Pequot War Battle Sites | Orr, Charles, Ed. The History of the Pequot War. Cleveland, 1897; RootsWeb

- Pequot Fort | Artist: John Underhill, 1638; Library of Congress

© 2020 Small Planet Communications, Inc. + Terms/Conditions + 15 Union Street, Lawrence, MA 01840 + (978) 794-2201 + planet@smplanet.com